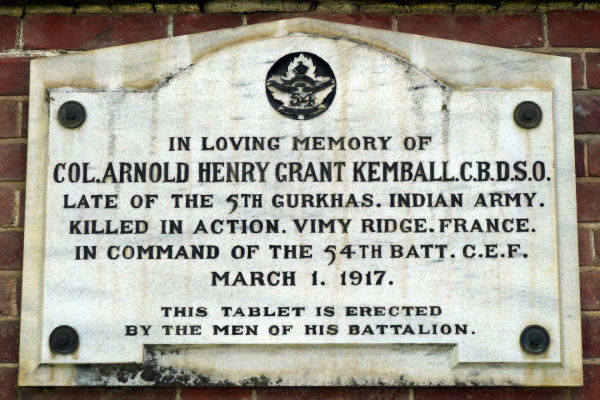

Now a seasoned battalion with the success at Desire Trench behind them and a DSO awarded to their commanding officer, the 54th was transferred to the sector opposite Vimy Ridge. 1917 was to be the British Army’s turn to try to apply it’s tactical lessons against the German line in a series of attacks which were to continue throughout 1917. The first of these was given to the Canadian Corps and was to be an assault on Vimy Ridge.

Canadian soldiers following a tank during the attack on Vimy Ridge – 1917

Thorough preparation was to be the key and to this end, elaborate communication trenches and tunnels were created in order to deliver a mass attack of troops, supported by a barrage of artillery, on the day. In order to understand what they were facing, the upper command ordered a series of raids across no man’s land. One such raid was to be conducted by four battalions of the 4th Division, including Kemball’s 54th. A special feature of this attack was to be the use of phosgene gas, a deadly nerve agent with the ironic smell of new mown hay.

In his book No Place To Run:The Canadian Corps And Gas Warfare In The First World War, Tim Cook describes this raid in detail as an example of futility and incompetence.

The Canadian Corps continued a campaign of raiding in February and March 1917, which not only cowed the German defenders but taught important battlecraft tactics to the Canadian infantry. The raiders were forced to devise new methods of getting across the fire zone, learned the importance of having every member know his role in the operation, and mastered the difficult task of coordinating the infantry and artillery to work in combination. A series of raids made by the 4th Brigade on 17 January and the 10th Brigade on 13 February were very successful in capturing prisoners, obtaining information, and killing Germans. The raids were not without their costs, and it was usually the best officers and troops who suffered when things went wrong, as they sometimes did. Yet as the Canadians were gaining confidence in their superiority over the Germans, the 4th Division was putting the finishing touches on its operation against Hill 145, one of the highest points on Vimy Ridge.

The oversized raid was to consist of 1,700 officers and men from the 54th, 72nd, 73rd, and 75th Battalions, preceded by a bombardment and a release of canister gas to achieve surprise and overcome the German defenders. The fact that the assault against Hill 145 would be moving uphill does not appear to have worried General David Watson or his General Staff Officer 1 (the highest ranking staff officer) Edmund Ironside. The bristling fortified defenses and interlocking machine gun nests that the Germans had reinforced for two years were deemed a powerful position, but it was assumed that the poison gas would paralyze the defenders so the infantry could close and do battle. Despite the largely unsuccessful use of gas clouds in this way to date, the DGO (Divisional Gas Officer), Lieutenant Henry V.I. Beaumont, gave little if any warning that the gas, which followed the contours of the ground and sank into crevices and shell holes because of its weight in comparison to air, would require a stiff breeze to move it up the hill. Gas remained a misunderstood weapon and, because of its technical and scientific nature, it was shunted to the periphery, to be used by “specialists” who were seen more as chemists than soldiers. Bent on a “raiding mentality,” the 4th Division’s staff officers overlooked the obvious disadvantages of their plan, perhaps because their gas specialist gave no reason for concern. More likely, they assumed that it would work because they needed it to. The raid’s planners proceeded to place their faith and their men’s lives behind a wave of gas.

There was little understanding of chemical warfare by senior commanders. When gas was implemented, senior officers always hoped that it would emulate the first gas cloud release of the war, when two whole divisions were routed. Although poison gas was still a weapon that inspired terror, better gas discipline and respirators ensured that no such rout would occur again. Equally detrimental, the Canadian staff officers and commanders had neglected training their soldiers in any doctrine on how to work in conjunction with the gas. Yet given their formidable positions on the hill and its defenses, gas was needed because other, more conventional weapons could not guarantee success. Gas was not the armament of choice, but of desperation; ill placed hope created delusions that outweighed all logical assumptions.

It fell to the pack mules of the army- the infantry- to once again lug up thousands of hundred-pound metal cylinders. Although everything was organized by the night of 25-6 February, the wind remained uncooperative and the British attack gas specialists of Company “M” were forced to delay the release. As the raiders waited for the signal, one wonders how much faith they put in their orders, which had told them that “fifteen tons of gas was to sent over to strike terror into the black heart of the enemy. The first wave was to be of deadly poisonous gas that would kill every living thing in its path: while the second would corrode all metal substances and destroy guns of every description.” This was the official line from both commanders and gas officers, which, when combined with the constant rumors that percolated at the front with regard to new, lethal gases being introduced, continued to foster the belief that gas would be the catalyst to victory.

Some had a better tactical appreciation of the situation, and at least two of the four battalion commanders argued that the raid was impractical. Lieutenant Colonel A.H.G. Kemball, the commander of the 54th Battalion, objected to Brigadier-General Victor Odlum, commander of the 11th Brigade, that because of the unpredictable wind the raid should be postponed and more artillery should be brought to bear on the German lines. Equally concerned, Lieutenant Colonel Sam Beckett, the commander of the 75th Battalion, not only believed that the surprise attack no longer a secret but also feared that his troops had insufficient training with gas. Aware that two of his experienced and decorated battalion commanders were unhappy with the plan, Odlum questioned his orders by writing to and visiting Lieutenant-Colonel Edmond Ironside. Despite getting into a heated argument with Ironside-bordering on insubordination, as one officer reported- Odlum received no definite answer to his central concern about how, if the gas failed, his men were to get across No Man’s Land before the enemy barrage opened up. A future chief of the Imperial General Staff of the British Army, the massive Ironside, who stood six feet four inches and weighed 220 pounds, had a firm hand on controlling the division, and, as some junior officers noted, had undue influence over Divisional Commander David Watson. Ironside, possibly on orders from Watson, refused to entertain ideas about postponement- too much planning and hope were riding on the raid. Hoping for the best, the attack groups remained at the ready. Thus, two experienced battalion commanders, who were close to the front and saw the formidable defenses their men were up against, were ignored by the staff officers who relied on a dubious weapon to overcome defenders who had spent two years fortifying their position. Such actions did not bode well.

The inconsistent weather, a superior German position, and the normal difficulties associated with a large-scale assault, especially one that involved hundreds of men carrying clanging metal objects to the front, meant that the surprise of the attack- the fundamental aspect for the gas component to succeed- was lost. Nerves began to fray as the interconnected infantry, artillery, gas specialists, and commanders waited hour after hour for the start signal.

The waiting also took its toll physically: the 12th Brigade had three killed and twenty-two wounded in stray shelling alone. Moreover, during the wait at least one German artillery barrage searching Canadian lines punctured some of the canisters. A sentry noticed the gas and awoke his platoon, but not wanting to alert the Germans they could not raise a gas alarm. Word was quietly passed along the trenches, but it failed to reach a small group of infantrymen in the path of the wayward cloud. All were poisoned and one man suffocated to death. The Canadians were learning the hard way that employing infantry and gas was a dangerous proposition. Still, the attack remained unchanged; the raiders were to follow behind the second of two gas clouds into the German trenches. It was planned that the second release would catch many of the Germans unprepared, exhausted and lethargic from the ordeal of the first gas cloud.

The hours of waiting turned into days- a full three days passed before the 4th Division’s Headquarters received the code word “CAT” from the British gas specialists to indicated proper weather conditions. Finally- at 3 a.m. on 1 March the Special Companies’ gas sergeants, wearing red, white, and green brassards for identification, released 1,038 cylinders of White Star (chlorine and phosgene) gas into a stiff breeze of nine miles per hour, which in some areas carried it quickly over to the German lines. Unfortunately for the Canadians, the German defenders had only recently been issued orders to combat a gas attack: “As soon as the alarm is given shoot up red and green flares. Our artillery will fire into the gas cloud and on the hostile trenches.” True to orders, the German counter-barrage fell on the Canadian lines and immediately punctured three canisters, gassing several Canadians and gas specialists and further lowering the infantry’s impression of their chemical agents.

Messages sent back to divisional headquarters by forward observers noted that the Germans, adopting the new gas defense, immediately fired red SOS flares and kept their riffle fire “fairly regular” until the gas had moved past their lines. The raiders were to go into No Man’s Land at 5:40, forty minutes after a second discharge of gas. But minutes before the second gas cloud was to be released the wind changed and the second wave of gas could not be liberated. In the 12th Brigade’s sector, however, the message to hold off was not received, and when the gas was released it slowly moved up the ridge only to stop and lazily float back toward the Canadian lines, eventually drifting through the waiting soldiers of the 11th Brigade. A private from the 102nd Battalion, Maurice Bracewell, remembered with terror as the gas turned and seeped into the Canadian lines: “Our front lines got all the gas, the front trenches were saturated with it”. Although, in the confusion, the gas casualties suffered by Canadians were not recorded, they were probably light, considering most men were equipped with the very effective SBR. Yet because the gas was so dense in the crowded trenches, the raiding parties, mostly from the 73rd Battalion, were forced to leave their safety, suffering additional casualties from conventional weapons as they proceeded overland until they found their assembly points.

Mistakenly thinking that the second gas attack had blown through the German ranks, one officer of the 50th Battalion remembered years later that he and his men, who were acting as a reserve on the flank of the 75th Battalion, believed the orders passed down from higher commands that “we were just going to jump over the top and pick up all these gassed Germans.” When he looked across the 250 yards of No Man’s Land, just minutes before the first wave of 75th Battalion men were to go over, he was shocked to see the Germans tightly packed in their trenches, bayoneted rifles aimed at his lines. The Canadian raiders, already committed to battle and spurred on by their earlier dominance, continued with the plan and hoped that the Germans had been sufficiently overcome by the first wave of gas. They were not.

On the day of the assault, the situation was this: the German’s had been alerted to the use of gas by the clanking of the cylinders being carried up to the line; the Canadians had been in the forward trenches for three days exposed to leaking gas and German shell fire; the artillery had made a poor job of breaking up the enemy wire; and the markers placed in no man’s land on the original day of attack were being used by the Germans for directing their machine gun fire.

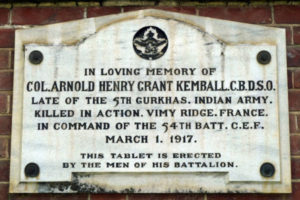

Lieutenant Colonel Kemball, his request for postponement and the use of more artillery refused, felt that he was honour bound to defy orders to remain behind and go with his men in order to lead them through the wire and perhaps mitigate the inevitable disaster. Sam Beckett of the 75th felt the same. That night, alone in his dugout, he wrote a letter to his wife.

My own darling,

We have moved forward to attack tomorrow – at dawn following gas clouds. It is a dirty job and all one can say is that the beastly Germans started using it. I am not in favour of using it at all but if it is done at all it ought to be on the grand scale so as to do real harm to the enemy but we are just playing with it and only putting it over on a front of little more than a mile. Everything depends on the wind being just right when done as we are doing it and the odds are we won’t do any real damage. I am going over with the attack as there is a difficult job on our right and although I am not supposed to go I think both men and officers would expect me to do so after the rot that was put in the Gazette about me. One thing is the gas cloud will probably miss the right so we will first have a straight fight for it and if the officers survive the advance we will have the pleasure of trying to knock the stuffing out of Fritz.

Of course by the time you get this you will know how I have fared, but if I should get knocked out remember that is no more than is to be expected at this game and that one has to do one’s job to the best of one’s ability without too much regard for one’s skin. I have never ceased to love you and am always thinking of you all. Nothing would please me better than for the war to end tomorrow and to get back to Canada in quick time. Anyhow I don’t worry about you all financially as you are entitled to a good pension from Canada in addition to the Indian and King’s ones, about which you will find pamphlets in my suitcase or somewhere. Mother’s estate has not been settled up yet but there is about 300 pounds in addition to the Trust money. Eva has promised to leave half her money to the girls so eventually you will be on easy street. If you are wise you won’t be in a hurry to get rid of the ranch and don’t let yourself be persuaded to get out of it until the trees are at least 4 or 5 years older. Don’t try to farm but have the trees looked after with the idea of having something to sell that is worth buying and you then ought to get a good price for the place if you feel like quitting. If you sell, do it through a lawyer and you won’t get into difficulties.

Good bye dearest, heaps and heaps of love and kisses.

At zero hour the Canadians went “over the bags” in a headlong assault into massed enemy fire. The gas has been expected to paralyze the enemy, and white flags had therefore been set up to mark the gaps in the wire. They drew the Canadians into natural killing zones as German machine-gunners were drawn to those hard-to-miss targets. In order not to alert the enemy, there had been only a sporadic attempt at clearing the barbed wire with explosives. Hundreds of Canadians were mowed down as they struggled through the ill-cleared razor-wire of No Man’s Land. In less than five bloody minutes the 54th battalion alone lost its commanding officer, two of the four company commanders (the other two injured), and close to 190 men, remembered Sergeant Major Alex Jack. Other attack groups made up of the other three battalions suffered similar fates.

The futile assault degenerated into a mad scramble, but throughout it the Canadians displayed their reputation for dogged tenacity that they had won on earlier battlefields. Despite their relentless push forward, it was a grim time as friends and companions who had survived the horror of the Somme were cut down in swaths. Added to the confusion of losing most senior commanding officers, vapours of the first and second wave of gas clung to shell holes in no Man’s Land so that the attackers had to advance through their own lethal agent. In addition, the Germans fired gas shells into the assembly trenches of the attacking Canadians. Although this caused few casualties, it forced the raiders to don their respirators, which left them almost blind as they ran through the lingering gas, desperately searching for gaps in the wire as bullets and shells rained down. Despite this frontal attack, the Canadians cleared a 500-yard section of the German trenches in hand-to hand fighting. The inability to reinforce the raiders and the general breakdown of the assault meant the retreating Canadians, jumbled together from the four battalions, fought a running battle with the Germans. Cut off from their own lines by counter-attacks, the Canadian infantry risked having all survivors captured. A successful rearguard action by several officers allowed dozens of men to escape, but as one trench warrior observed, “we had very heavy casualties, especially among the officers.” As the futility of the attack became apparent, front-line officers, from battalion commanders to the lowest lieutenant, sacrificed themselves for their men.

Those soldiers wounded in No Man’s Land crawled to shell holes for safety and in the process often fell victim to their own gas, which pooled in the mucky depressions. Stuck in a crater while the Germans sniped at anything that moved, private Stanley Baker remembered watching the men in his large hole slowly being killed as exposed heads and backs were blasted by sharpshooters. Employing one of the corpses for cover, he used his helmet to dig a shallow trench though the muck to reach another hole in the rear. The lingering gases made him cry and vomit, but he finally wormed his way back to the Canadian line later that night. As soldiers dragged themselves into the trenches, their chlorine tarnished brass buttons were just as noticeable as their ashen faces and bluish lips. The chaos of battle, with smoke and fire obscuring vision, and gas masks clouding up and reducing the intake of breath, had forced many of the soldiers to remove their respirators for periods of time in a desperate need to locate gaps in the wire. Masks could not be worn all the time. Any heavy exertion, like running up the ridge while under fire, provoked near strangulation effects, as not enough oxygen entered through the filters. The nature of enemy fire forced all to take cover; many who did not quickly move from their corrupted shell holes never left their informal graves.

When the roll was called the next day, the full extent of the disaster was known; the four attacking battalions suffered 687 casualties. Those men who were not too numb with exhaustion or suffering from the lingering effects of gas began to question the whole raid. The War Diary of the 54th critically remarked that the “first discharge of gas apparently had no effect on the enemy,” but more important, the question arises as to why anyone would have thought any differently.

In order for the Canadians to gather up their wounded and dead, a truce was arranged. The Germans, recognizing Kemball’s heroism, brought down his flag-draped body with an honour guard. He was buried wrapped in a simple grey blanket, along with those of his officers and men who had suffered the same fate, at the nearby Villers Station Cemetery. His grave was marked by a standard issue wooden cross which was later replaced by a more permanent tombstone.

Tim Cook continues:

By this point in the war, both the Canadians and Germans were equipped with very good respirators that made the use of canistered gas almost useless unless employed against poorly trained or surprised opponents. The distance of 200 to 250 yards between the lines meant that the enemy had one to two minutes before the vapours reached them. That was certainly enough time to don respirators, especially if they were aware of the possible use of gas. The series of delays, combined with German intelligence gathered from raids, prisoners, and simple observation, had already cancelled the surprise factor. As the full results of the debacle circulated, gas was viewed with loathing; it was supposed to be a super weapon that was to have made the raid a walk-over; instead, it had led to an absolute disaster. If despised by the front-line troops, gas was also universally condemned by the commanders in the rear. In an after-battle report, Brigadier- General J.H. MacBrien, commander of the 12th Brigade, noted that the initial “discharge brought the enemy up out of his dugouts and made him suspect and prepare to resist an attack or raid.” His equal, the commander of the 11th Infantry Brigade, Victor Odlum, was more empathetic and raged that the infantry should never have been sent over for it was obvious with the rifle fire coming from the German lines that the defenders had not been incapacitated by the gas. Major-General David Watson, commander of the 4th Division, echoed his brigadiers- despite his earlier dismissal of Odlum’s concerns- and later wrote that “gas was overestimated, and too much reliance was therefore placed on it.” Such comments were correct in exposing the limited role of gas clouds as tactical weapons, but it did little for the hundreds of Canadians who were rotting on the battlefield due to faulty planning.

Gas remained as double-edged sword that, when employed properly, could be a very useful weapon. However, the infantry hoped to never see the vile stuff again. General Byng, always a favorite among the rank and file, recounted later: “I consider I was wrong in thinking the gas would be more effective on the morale of the enemy than events proved. I was under the impression that this gas used in large quantities had the effect of placing men temporarily out of action.” As a result of the failed raid the Canadians decided, and rightly so, against combining gas and infantry attacks for the rest of the war. This did not preclude the use of gas shells in barrages or counter-battery work, but the infantry commanders chose to return to proven methods of combining artillery, mortars, and machine guns. When the Canadians went “over the top” at Vimy, they would not be blind cattle mounting the slaughterhouse ramp like the men of the 4th Division five weeks earlier. They were to be thinking, reacting soldiers, whose commanders relied on the polished policy of soldiers leaning into massive artillery barrage, rather than an untrustworthy gas cloud.

The devastated 4th Division did not have enough time, or enough experienced officers, to train and integrate new soldiers into the units that had been so damaged in the raid. Not only were the results of the raid destructive to those four units and the morale of the division generally, but, more important, it illustrated the exceedingly poor leadership from the Canadian commanders. The naïveté of the 4th Division’s staff officers was shocking, and their flimsy understanding of the concept of poison gas resulted in needlessly wasted Canadian lives. Perhaps the use of this exotic weapon stemmed from a desire to distinguish the most junior division from the rest, but the operational disaster that resulted left the survivors wary of both gas and of the fools in their comfy camps behind the line who believed in it. Gas had clearly been overestimated, yet it was a weapon that had been used on the Western Front for almost two years. The success of gas in several sensational battles perverted its true role and allowed the staff officers in the rear to trick themselves into believing that they had found the solution to the tactical problems of their raid. Some of the blame must also fall on Lieutenant Henry V.L. Beaumont, the DGO who pushed to have the gas incorporated into the assault. Corporal A. Selwood of the 72nd Battalion remembered seeing Beaumont “feeling sorry for himself” when the news of the gas-induced disaster began to seep back to the front and Selwood remarked that the raid destroyed his hope of winning a Military Cross, which he had been talking about before the battle. Equally grievous, the failure to heed the advice of experienced front-line officers showed a dangerous rigidity within the division. The success of the 4th Division in later battles, after they had recuperated from their lashing during the March raid, proved that they had learned the requirement for meticulous planning, the need for accurate battlefield intelligence, and, finally, the necessity of a combined-arms doctrine based on artillery and infantry working in close conjunction. Still, for the poor bloody infantry in the trenches, gas was further distrusted and feared, and there were few survivors in the 4th Division who would not have agreed with Lieutenant Howard Green of the 54th Battalion, who remarked that the raid “was just a proper slaughter.”

Shortly after the failed battle for Hill 145, on 3 May 1917, the Canadian Corps took the last step in the organization of its Gas Services by appointing a Canadian Corps chemical advisor, Captain W. Eric Harris. Prior to the war, he had been an instructor in Chemistry at Ridley College, and before his current position he had been assistant chemical advisor at First Army Headquarters. Harris was now attached directly to the Corps Headquarters as the most senior officers of the Canadian Gas Services. His job was to work directly with the general staff at Canadian Corps Headquarters in organizing and managing the dissemination of gas information, while also “standardizing the work of the Divisional Gas Officers.” Harris was to play an important role in entrenching effective gas discipline in Canadian troops. Throughout the war he campaigned against the slackness of commanders and junior officers in failing to enforce the gas discipline needed to ensure survival on the battlefield. In addition, he became a figurehead through which the Gas Services could implement vital changes. Although the four DGOs were generally effective in carrying out gas discipline, not one of them could organize reforms for the whole corps. The creation of a chemical advisor changed all of that. Harris arrived at the Canadian Corps on 26 March and found to his dismay that the Canadians were about to undertake their most ambitious attack of the war to date.