Ginger Goodwin- Advocate for Worker’s Rights

Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin was born on May 10, 1887, in Treeton, England. He moved to Canada at an early age and started working in coal mines in Nova Scotia, Alberta & BC. After experiencing challenging working conditions in the mines, he was motivated to take political action for the benefit of his fellow workers. He dedicated his life to the overthrow of capitalism and to workers rights. He was a pacifist, anti-imperialist, socialist and trade unionist.

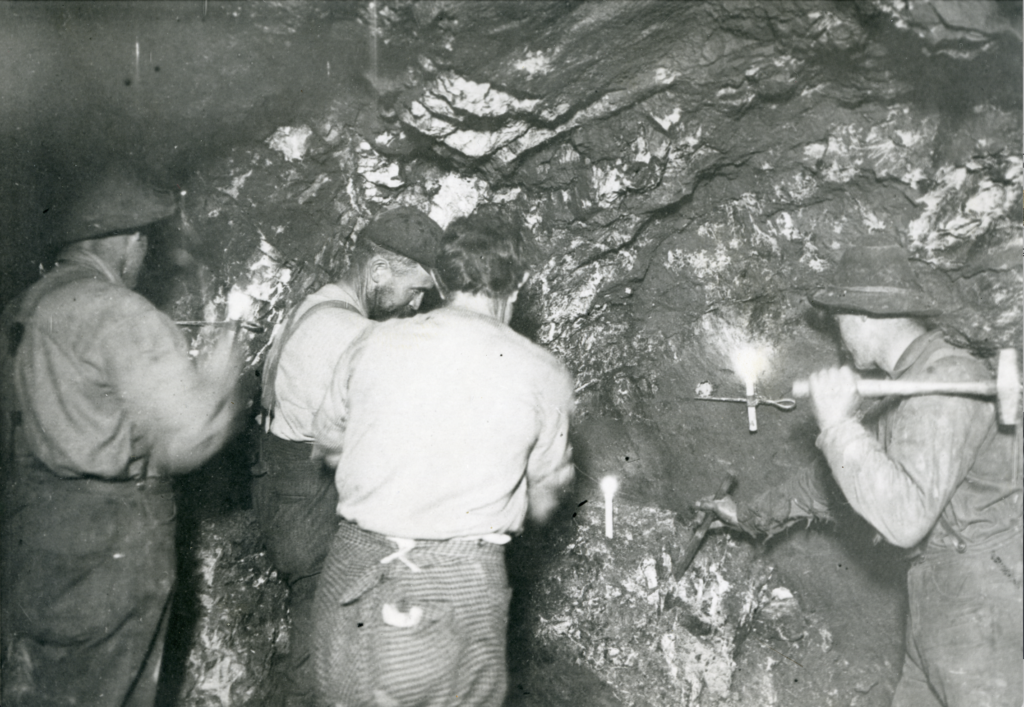

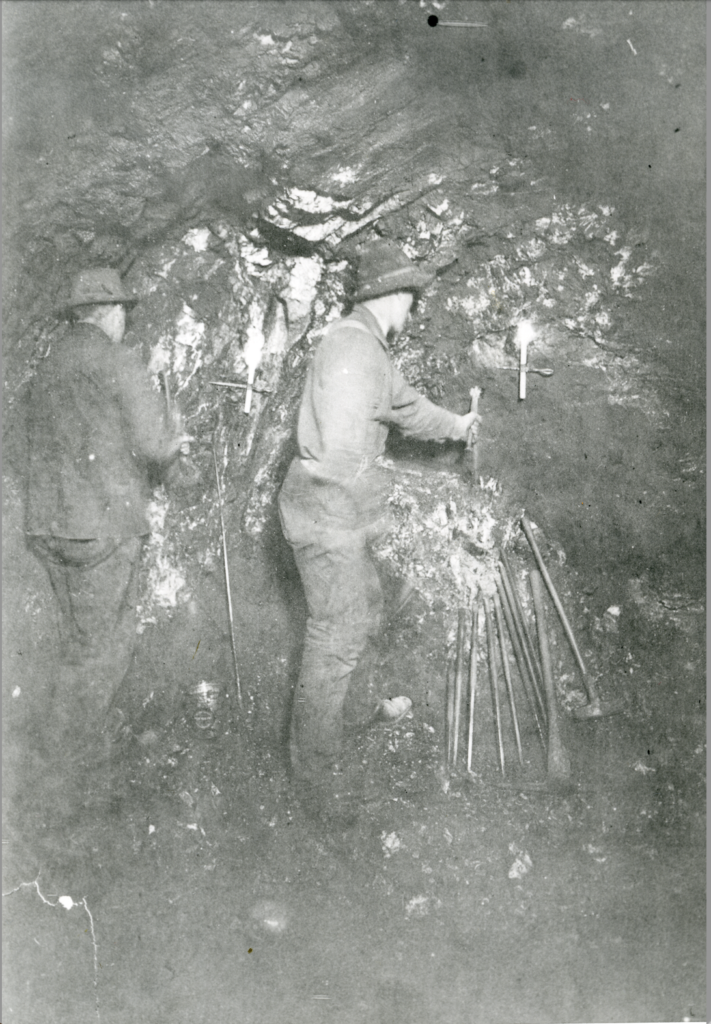

Ginger’s early days as a youth in the the Coalfields of Yorkshire helped him to understand the importance of workers rights and the differences between the lives of the working class and the bourgeoisie. He naturally followed in his fathers footsteps by working in the mines at the young age of 12 when he was just out of school. His father, Walter, was a manual labourer in the coal mine, where he worked long days extracting coal from the earth. As this was the era prior to mechanization, the work was even more taxing on the body and posed a greater threat to the workman’s safety & well-being. Class consciousness was instilled in Ginger from a young age, as he saw strikes and workers being disrespected at the hand of the bosses in his day to day life as a child. He witnessed workers who were striking being evicted from company housing to make room for strikebreakers, and he saw clearly what could happen to workers who advocated for their own interests. Rather than accepting these conditions, however, Ginger became an activist for workers rights and class solidarity and spent his working days trying to give a voice to his fellow workers.

Ginger started work in England as an underground pony driver through his teens, where he supplied coal tubs to the coalface and brought the coal back. The ponies lived largely underground in poor conditions and only when the workers were striking were they brought out to pasture (human workers were apparently not the only ones to benefit from the strikes). In 1913, more than 70,000 ponies were working in British coal mines.

Ginger (his nickname given for his bright orange hair) departed England in 1906 and arrived, via Glasgow & Newfoundland, in Halifax on September 1, 1906. The journey took 10 days. At this time, many British men made their trip across the Atlantic in search of a better life on the North American continent, where work and financial opportunity were said to be waiting. The experiences in the mines out east further radicalized Goodwin, and gave shape to his early experiences of being an exploited coal worker. He moved west to BC in 1910 in search of better conditions and to further his interest in advocating for his fellow workingmen in the mines.

Dangerous conditions, workplace explosions and deaths were unpleasant realities of in the mines. After finding work in the Dunsmuir Pits on Vancouver Island, Ginger soon became involved with attempting to organize a union and taking a leadership position in a large strike. He was consequently blacklisted from further work in the region. Jobless, he managed to find work in the Fernie coal mines and subsequently the Cominco Smelter in Trail, where his socialist views continued to grow.

After being blacklisted from the coal mines on Vancouver Island he managed to find work at the Trail smelter in 1916, where his political action continued. He was a member of the socialist party and was quoted in 1916 by the Trail News as saying that “the interests of the workers and that of the capitalists cannot be harmonized”. Because he was a strong speaker and gave voice to the views held by many, he was elected secretary of the Trail Mill & Smeltermen’s Union. Previously lacking in the workforce in Trail was a political consciousness that would allow workers to understand the conditions of their exploitation. Ginger Goodwin was integral to spurring the worker’s understanding and knowledge of their deplorable conditions, and Goodwin was able to enunciate how there could be a different lived reality to the one currently in place. Workers could advocate for their own safety, wages and hours- though the task would prove not an easy one management put profit and productivity above the health and safety of their employees.

It is important to note that, according to Marxist theory, the union is an imperfect & incomplete vehicle for the working class to achieve one of its central goals which is to overthrow capitalism. Goodwin was acutely aware of this, but he believed that capitalism being the economic model of his time, he was forced to secure workers rights through unionization. However, his ultimate goal was certainly to overthrow capitalism. In short, Goodwin’s goal was to overturn the model, believing it to be predicated on exploitation, class division, wage labour, and private property.

He saw firsthand in both the mines and smelters of BC in the early 20th century that the conditions were deplorable and that collective solidarity was needed to achieve workers rights. On the other hand, from the smelter owner’s perspective, the growth potential of their companies was hindered only by the limits put in place to protect workers. It was always in their interest to exploit those who have less power in return for financial gain.

As Goodwin stated it: “we know that all this misery is the outcome of someone’s carelessness and that someone is the capitalists, those who own the machinery of production… This class of parasites have been living on the blood of the working class, they are responsible for the conditions existing at the present time… To throw this system over we have got to organize as a class and fight them as class against class… and our weapons are education, organization and agitation… and the principles of Socialism, for it is necessary that you know when to strike and how to strike, and if we have not these weapons when the time comes, we shall not be able to predict the outcome of the fight… we have the power and the lever to overthrow the existing society” (Mayse, 62).

Strike in Trail

The strike at the Cominco smelter in Trail began on Thursday the 15th of November 1917. Tensions between the management and the union had reached an irreconcilable level, resulting in the strike of 1200 men. This was the first time that the smelter had ceased production in 20 years. As reported in the Trail News the morning after the strike; “not a wheel is turning today in any part of the big works”.

The core of the dispute was the eight-hour work day, as well as improved wages, though the perception of the company was that some employees were avoiding conscription. Ginger Goodwin was initially classified as unfit for service, as he had tuberculosis for over two years and had lasting issues with his lungs from his previous work in the mines. Perhaps at the hand of the company, after eleven days of striking, he was re-assessed and classified as fit for combat, and he was ordered to report for military duty.

As a pacifist and socialist, Goodwin saw little good in participating in the war, and he saw little difference between sending men into the mines than into the battlefield. At the end of the day, both of these realities put working class people in danger for the benefit of the ruling elite. Goodwin was quoted as saying “Why should the working man become cannon fodder while bosses lined their pockets?”. In short, socialists and labour leaders such as Goodwin believed that the war was being fought to defend the capitalist system and consequently they rejected mandatory conscription on these grounds. “War is simply part of the process of Capitalism,” he wrote. “Big financial interests are playing the game. They’ll reap the victory, no matter how the war ends.”

The strike at Cominco ended on the 21st of December, without the workers receiving what they had initially fought for (the eight hour workday). In the end, the eight hour workday was only implemented when it became law, showing how management put profits and productivity above the desires and livelihood of their workers. Cominco management claimed positive reconciliation, but, in reality many people who were promised a job upon ending the strike were left unemployed: “Over 500 men were not called back. Declining prices were part of the reason; the destruction of the union, was, however, the most important rationale” (Scott, 78).

Ex-strikers were blacklisted from work at the smelter and found it very hard to get by even in surrounding towns. Ginger Goodwin and other strike leaders fled town after hearing news of their mandatory conscription. In Ginger’s case specifically, he fled o Vancouver Islantd, near Cumberland, where local people fed and cared for the draft-dodgers who hid in the surrounding forests. A warrant his arrest was issued, supposedly only for his avoidance of the draft, however it has been speculated that the government viewed his radical views as a threat.

Eventually, Ginger Goodwin was killed by lieutenant Dan Campbell at the age of 31 in 1918. The claim is that Ginger pulled a gun first and that Campbell shot in self defence. In many labour circles, however, the event was seen as a murder and as an attempt of the government to reduce the collective bargaining rights of workers (as Goodwin was integral to this movement in the province).

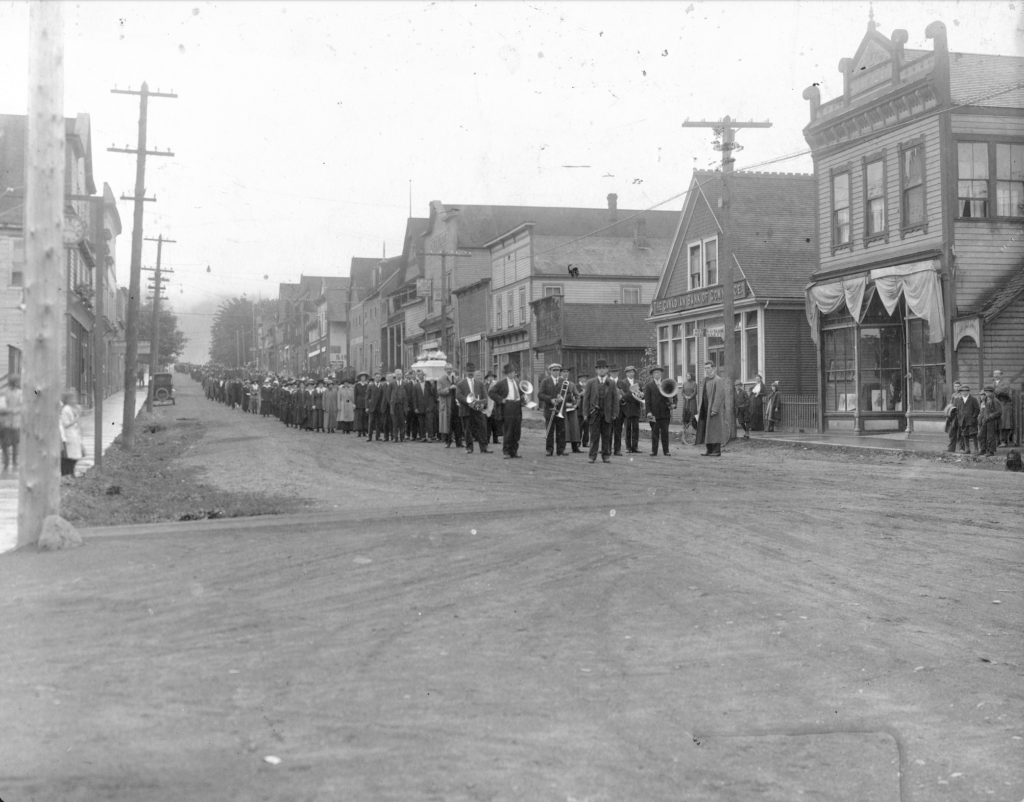

While the death of Ginger Goodwin was untimely and likely politically motivated, it did create a lasting impact on workers in BC and across Canada. His death inspired the first general strike, held in Vancouver on August 2nd, 1918. This strike then inspired the Winnipeg general strike of 1919 and brought to light many other labour issues. He is viewed as a martyr for worker’s solidarity and his lasting legacy is felt to this day. In 1996, a strip of highway that passes through Cumberland was named “Ginger Goodwin Way”. The Liberal government took the signs down in 2001, perhaps since they realized that the politics that Goodwin stood for were still a threat to them. The NDP government, however, reinstalled the signs in June 2018. Ginger Goodwin has since been seen as a person who died for resisting the unequal and exploitative economic system of the time. His legacy has served as a reminder to continue to resist and take seriously the working conditions and exploitation prevalent in our society.

Selwyn G. Blaylock

Selwyn Blaylock was born in 1879 in Quebec and graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Science from McGill University in 1899. Seeing British Columbia as a province with potential for expansion in mining and natural resources, he decided to leave Montreal for the growth potential of the West, specifically Trail. His first job was as an Assayer in the Trail smelter, which had recently been purchased by the CPR from Augustus Heinze. After two years as an Assayer, he was promoted to the position of Chief Chemist and over the years rose through the management ranks of Cominco. He worked at the Hall Mines Smelter in Nelson, the St. Eugene Mine, and later the Sullivan Mine in Kimberley as well.

Blaylock’s most important contribution to the mining industry in BC was the development of a process to extract the high zinc content from the ore of the Sullivan Mine in Kimberley. The Sullivan Mine was discovered in 1892, and its complex silver-lead-zinc ore proved to be challenging to work with. The ore failed to be metallurgically reduced in several attempts, as a result of its high zinc content. A special smelter was made in Marysville, but by 1908 it was closed and deemed a failure. When the Sullivan was taken over by Blaylock, he managed to research and develop a method to extract the zinc from the complex ore. By 1920 he had developed this process fully, and the mine went back into business and the ore was then treated in the smelter at Trail. It was transported via CPR railway.

Blaylock managed to work with the mines and smelters in a period of war and economic depression, and it is no small feat to have been able to keep these operations running in such trying times. He is remembered for placing emphasis on workers relations, however, his company-backed union was not without issue. After the 1917 strike, management at Cominco, and specifically Blaylock himself, formed what was called the Workmen’s Cooperative Committee. This was, to the company, a way of offering their employees access to a ‘union’ while at the same time having control of its operations and bargaining power.

Companies had to, by law, recognize unions, and Blaylock’s WCC could be perceived as a way to avoid workers creating a real union. In short, before workers could again band together on their own and form another threatening union, Cominco set up a company based union to ‘represent’ workers and to bargain with management over labour disputes. While this structure did provide workers with improved wages and some benefits, the power of the working class was significantly reduced, as a company-backed ‘union’ has within its structure an inability to be radical.

There is an inherent opposition of interest between the workers and owners and for radicals like Ginger Goodwin, words such as ‘respect’ or ‘fairness’ were not good enough, as under the system of capitalism and specifically wage labour these words lose meaning (for example, Blaylock lived in Tadanac, worked in a non-physical way, and made vastly disproportionate amounts of money at the expense of physical human labour in the smelter- under no ‘union’ contract could this be seen to be acceptable for a socialist like Ginger Goodwin).

The Workmen’s Cooperative Committee could be perceived as a representational union, perhaps in a reversal actually stripping workers of their rights and controlling them even further through the veil of union representation. Nonetheless, Blaylock is remembered as an important figure in mining, and did manage to keep his mines and smelter operating through two world wars and the Depression, in a period when many others failed.

Citations:

Leier, Mark. “To Praise Ginger Goodwin Is to Revere a Radical.” The Tyee. July 25, 2014. Accessed August 07, 2021. https://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2014/07/25/Ginger-Goodwin-Is-a-Radical/.

Marx, Karl. Economic Manuscripts: VALUE, PRICE AND PROFIT. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1865/value-price-profit/ch03.htm#c13.

Mayse, Susan. Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2019.

Scott, Stanley. “A Profusion of Issues: Immigrant Labour, the World War, and the Cominco Strike of 1917.” Labour / Le Travail, vol. 2, 1977, pp. 54–78. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25139897. Accessed 6 July 2021.

Solski, M., & Smaller, J. (1984). Mine Mill : the history of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers in Canada since 1895 / by Mike Solski and John Smaller. Steel Rail Pub.